automobile design 3d drawing 2000 felix kings canyon middle school

| Felix the Cat | |

|---|---|

Felix in his current design | |

| First advent | Feline Follies (1919) |

| Created by | Pat Sullivan Otto Messmer Joe Oriolo (redesign) |

| Voiced past | English Harry Edison (1929–1930)[1] Walter Tetley (1936) Jack Mercer (1959–1962) Ken Roberts (1959)[2] David Kolin (1988) Jim Pike (1990)[3] Thom Adcox-Hernandez (1995) Charlie Adler (1996) Don Oriolo (2000–2001) Denise Nejame (2000–2001; Baby) Dave Coulier (2004) Lani Minella (2010)[iv] Japanese Toshihiko Seki (2000–2001) Yumi Tōma (2000–2001; Babe) |

| In-universe information | |

| Species | Cat |

| Gender | Male |

| Family | Inky and Winky (nephews) |

Felix the Cat is a children'southward comedy drawing graphic symbol created in 1919 by Pat Sullivan and Otto Messmer during the silent picture show era. An anthropomorphic blackness cat with white eyes, a black body, and a giant grin, he was one of the most recognized cartoon characters in moving picture history. Felix was the offset animated character to reach a level of popularity sufficient to describe film audiences.[v] [6]

Felix originated from the studio of Australian cartoonist-picture entrepreneur Pat Sullivan. Either Sullivan himself or his lead animator, American Otto Messmer, created the graphic symbol.[7] What is certain is that Felix emerged from Sullivan's studio, and cartoons featuring the graphic symbol became big in pop culture. Bated from the animated shorts, Felix starred in a comic strip (drawn by Sullivan, Messmer and later Joe Oriolo) beginning in 1923,[eight] and his prototype soon adorned merchandise such equally ceramics, toys and postcards. Several manufacturers fabricated stuffed Felix toys. Jazz bands such every bit Paul Whiteman's played songs well-nigh him (1923's "Felix Kept on Walking" and others). In 1926, Felix became the first high schoolhouse mascot for the Logansport, Indiana Berries.

By the late 1920s, with the inflow of sound cartoons, Felix's success was fading. The new Disney shorts of Mickey Mouse fabricated the silent offerings of Sullivan and Messmer, who were and then unwilling to move to sound production, seem outdated. In 1929, Sullivan decided to make the transition and began distributing Felix audio cartoons through Copley Pictures. The sound Felix shorts proved to be a failure and the operation concluded in 1932. Felix saw a brief three-cartoon resurrection in 1936 by the Van Beuren Studios.

Felix cartoons began airing on American boob tube in 1953. Joe Oriolo introduced a redesigned, "long-legged" Felix, with longer legs, a much smaller trunk, and a larger, rounder head with no whiskers and no teeth. Oriolo also added new characters and gave Felix a "Magic Bag of Tricks" that could presume an infinite multifariousness of shapes at Felix's behest. The cat has since starred in other boob tube programs and in two feature films. As of the 2010s, Felix is featured on a variety of merchandise from clothing to toys. Joe'southward son Don Oriolo afterward causeless artistic command of Felix.

In 2002, Television receiver Guide ranked Felix the Cat number 28 on its "50 Greatest Cartoon Characters of All Time" list.[ix]

In 2014, Don Oriolo sold the rights to the character to DreamWorks Animation, which is now role of Comcast'south NBCUniversal partition via Universal Pictures.[10]

Cosmos [edit]

Feline Follies past Pat Sullivan, silent, 1919

A scene of Felix laughing, from Felix in Hollywood (1923)

Felix and Charlie Chaplin share the screen in a moment from Felix in Hollywood (1923).

The "Felix pace" as seen in Oceantics (1930)

Felix in the colour drawing Felix the Cat and the Goose That Laid the Gilt Egg (1936)

Children with Felix the True cat toy, Nielsen Park Embankment, Sydney, NSW, 1926.

On 9 November 1919, Chief Tom, a prototype of Felix, debuted in a Paramount Pictures brusk titled Feline Follies.[11] Produced by the New York City-based blitheness studio owned by Pat Sullivan, the cartoon was directed by cartoonist and animator Otto Messmer. Information technology was a success, and the Sullivan studio rapidly set to work on producing another film featuring Master Tom, in Musical Mews (released 16 November 1919). It too proved to be successful with audiences. Messmer claimed that John King of Paramount Mag suggested the name "Felix", after the Latin words felis (true cat) and felix (happy).[ citation needed ] The name was starting time used for the third film starring the character, The Adventures of Felix (released on xiv December 1919). Sullivan claimed he named Felix after Australia Felix from Australian history and literature. In 1924, animator Bill Nolan redesigned the graphic symbol, making him both rounder and cuter. Felix's new looks, coupled with Messmer's grapheme animation, brought Felix to a higher profile.[12]

[edit]

The question of who created Felix remains a affair of dispute. Sullivan stated in numerous newspaper interviews that he created Felix and did the key drawings for the character. On a visit to Australia in 1925, Sullivan told The Argus newspaper that "[t]he idea was given to me past the sight of a cat which my wife brought to the studio one day".[13] On other occasions, he claimed that Felix had been inspired by Rudyard Kipling's "The True cat that Walked by Himself" or by his wife's love for strays.[12] Members of the Australian Cartoonist Association have claimed that lettering used in Feline Follies matches Sullivan'southward handwriting[14] and that Sullivan lettered inside his drawings.[xiv] In add-on, at roughly the 4:00 marking in Feline Follies, the words 'Lo Mum' are used in a speech bubble by i of the kittens; this was a term for one's female parent not used by Americans, just certainly past Australians. Yet Messmer claimed to have single-handedly drawn Feline Follies from home, raising questions as to why an American would apply the term 'Mum' in a cartoon he solely drew himself. Sullivan'south supporters likewise say the instance is supported by his 18 March 1917 release of a cartoon short titled The Tail of Thomas Kat more than two years prior to Feline Follies. Both an Australian ABC-Idiot box documentary screened in 2004[15] and the curators of an exhibition at the State Library of New South Wales in 2005 suggested that Thomas Kat was a image or precursor of Felix. However, few details of Thomas have survived. His fur color has not been definitively established, and the surviving copyright synopsis[ citation needed ] for the short suggests significant differences between Thomas and the later on Felix. For case, whereas the later Felix magically transforms his tail into tools and other objects, Thomas is a non-anthropomorphized cat who loses his tail in a fight with a rooster, never to recover it.

Sullivan was the studio proprietor and—every bit is the example with well-nigh all moving-picture show entrepreneurs—he owned the copyright to any creative piece of work by his employees. In common with many animators at the fourth dimension, Messmer was not credited. After Sullivan's death in 1933, his estate in Australia took buying of the character.

Information technology was non until after Sullivan'south death that Sullivan staffers such as Hal Walker, Al Eugster, Gerry Geronimi, Rudy Zamora, George Cannata, and Sullivan's ain lawyer, Harry Kopp, credited Messmer with Felix's creation. They claimed that Felix was based on an animated Charlie Chaplin that Messmer had animated for Sullivan's studio before on. The down-and-out personality and movements of the true cat in Feline Follies reflect fundamental attributes of Chaplin'southward, and, although blockier than the subsequently Felix, the familiar black trunk is already at that place (Messmer found solid shapes easier to breathing). Messmer himself recalled his version of the cat's cosmos in an interview with blitheness historian John Canemaker:

Sullivan'due south studio was very busy, and Paramount, they were falling behind their schedule and they needed ane extra to fill up in. And Sullivan, existence very busy, said, "If you desire to do it on the side, you lot can do any little thing to satisfy them." So I figured a cat would exist about the simplest. Make him all black, y'all know—you wouldn't need to worry about outlines. And one gag subsequently the other, you know? Cute. And they all got laughs. So Paramount liked it then they ordered a series.

Further, Messmer told Canemaker that both he and Sullivan drew Felix based on models from the minstrel show tradition and the racist pickaninny caricature:

Pat Sullivan... started off on his own, doing his piddling Negro Pickaninny [Sammie Johnsin]. Which afterwards on became nearly Felix, at least in my mind anyway. Same kind of a, only he was a pickaninny. At present that was going along pretty good, merely it didn't through the S, that little anti-Negro feeling. They wouldn't run the Pickaninnies.[sixteen]

The tropes of minstrelsy were useful for creating a cartoon animal because they cued the audience to look a lively, amusing and rebellious character.[sixteen]

Animation historians back Messmer'due south claims. Among them are Michael Bulwark, Jerry Beck, Colin and Timothy Cowles, Donald Crafton, David Gerstein, Milt Grey, Mark Kausler, Leonard Maltin, and Charles Solomon.[17] No animation historians exterior of Australia have argued on behalf of Sullivan.

Sullivan marketed the cat relentlessly while Messmer continued to produce a biggy book of Felix cartoons. Messmer did the animation on white paper with inkers tracing the drawings straight. The animators drew backgrounds onto pieces of celluloid, which were then laid atop the drawings to be photographed. Any perspective work had to be blithe by hand, as the studio cameras were unable to perform pans or trucks.

Popularity and distribution [edit]

Paramount Pictures distributed the earliest films from 1919 to 1921. Margaret J. Winkler distributed the shorts from 1922 to 1925, the twelvemonth when Educational Pictures took over the distribution of the shorts. Sullivan promised them one new Felix short every 2 weeks.[18] The combination of solid animation, adept promotion, and widespread distribution brought Felix'southward popularity to new heights.[nineteen]

References to alcoholism and Prohibition were too commonplace in many of the Felix shorts, particularly Felix Finds Out (1924), Whys and Other Whys (1927), and Felix Woos Whoopee (1930), to proper noun a few. In Felix Dopes It Out (1924), Felix tries to help his hobo friend who is plagued with a cherry nose. Past the cease of the short, the true cat finds the cure for the status: "Keep drinking, and it'll turn blue".

In addition, the true cat was one of the offset images ever broadcast by television when RCA chose a Felix doll for a 1928 NBC experiment in New York'due south Van Cortlandt Park. The papier-mâché (afterwards Bakelite) doll was chosen for its tonal contrast and its ability to withstand the intense lights needed. It was placed on a rotating phonograph turntable and photographed for approximately ii hours each day; as a result, Felix is considered by some to be the world's kickoff TV star. After a one-fourth dimension payoff to Sullivan, the doll remained on the turntable for nearly a decade as RCA fine-tuned the picture's definition.[20]

Felix'southward smashing success also spawned a host of imitators. The appearances and personalities of other 1920s feline stars such as Julius of Walt Disney's Alice Comedies, Waffles of Paul Terry's Aesop's Film Fables, and especially Neb Nolan'south 1925 adaptation of Krazy Kat (distributed by the eschewed Winkler) all seem to accept been direct patterned subsequently Felix.[21] This influence also extended outside the United States, serving as inspiration for Suihō Tagawa in the creation of his character Norakuro, a dog with black fur. [1]

Felix's cartoons were likewise popular amongst critics. They have been cited as imaginative examples of surrealism in filmmaking. Felix has been said to represent a kid's sense of wonder, creating the fantastic when it is not in that location, and taking information technology in stride when information technology is. His famous pace—easily behind his back, head down, deep in thought—became a trademark that has been analyzed by critics effectually the earth.[22] Felix'southward expressive tail, which could be a shovel one moment, an exclamation mark or pencil the side by side, serves to emphasize that anything can happen in his world.[23] Aldous Huxley wrote that the Felix shorts proved that "[w]lid the movie house can do better than literature or the spoken drama is to be fantastic".[19]

Past 1923, the character was at the top of his movie career. Felix in Hollywood, a short released during that year, plays upon Felix's popularity, as he becomes acquainted with such boyfriend celebrities as Douglas Fairbanks, Cecil B. DeMille, Charlie Chaplin, Ben Turpin, and even censor Will H. Hays. His epitome could be seen on clocks (non to be confused with the Kit-Cat Klock) and Christmas ornaments. Felix also became the subject of several popular songs of the day, such equally "Felix Kept Walking" past Paul Whiteman. Sullivan made an estimated $100,000 a yr from toy licensing lonely.[19] With the graphic symbol's success as well emerged a handful of new costars. These included Felix's master Willie Jones, a mouse named Skiddoo, Felix's nephews Inky, Dinky, and Winky, and his girlfriend Kitty. Felix the Cat sheet music, with music by Pete Wendling and Max Kortlander and featuring lyrics by Alfred Bryan, was published in 1928 past Sam Fox Publishing Company. The cover fine art of Felix playing a banjo was done past Otto Messmer.[24]

Most of the early Felix cartoons mirrored American attitudes of the "Roaring Twenties". Ethnic stereotypes appeared in such shorts every bit Felix Goes Hungry (1924). Recent events such as the Russian Civil War were depicted in shorts like Felix All Puzzled (1924). Flappers were caricatured in Felix Strikes It Rich (1923). He also became involved in union organizing with Felix Revolts (also 1923). In some shorts, Felix fifty-fifty performed a rendition of the Charleston.

In 1928, Educational ceased releasing the Felix cartoons, and several were reissued by First National Pictures. Copley Pictures distributed them from 1929 to 1930. There was a brief three-cartoon resurrection in 1936 by the Van Beuren Studios (The Goose That Laid the Gilt Egg, Neptune Nonsense, and Bold Rex Cole). Sullivan did most of the marketing for the grapheme in the 1920s. In these Van Beuren shorts, Felix spoke and sang in a loftier-pitched, childlike vocalisation provided by and so-21-year-old Walter Tetley, who was a pop radio actor in the 1930s, 1940s and even 1950s (Julius on The Phil Harris-Alice Faye Show, and Leroy on The Great Gildersleeve), but later best known in the 1960s as the vox of Sherman on The Rocky and Bullwinkle Evidence 's Mister Peabody segments.[ citation needed ]

Felix every bit mascot and pop culture icon [edit]

The U.S. Navy insignia for the VF-31 squadron from 1948

Given the character's unprecedented popularity and the fact that his proper name was partially derived from the Latin word for "happy", some rather notable individuals and organizations adopted Felix as a mascot. The first of these was a Los Angeles Chevrolet dealer and friend of Pat Sullivan named Winslow B. Felix, who starting time opened his exhibit in 1921. The three-sided neon sign of Felix Chevrolet,[25] [26] with its behemothic, smiling images of the grapheme, is today ane of LA'due south better-known landmarks, standing watch over both Figueroa Street and the Harbor Freeway. Others who adopted Felix included the 1922 New York Yankees and pilot and actress Ruth Elder, who took a Felix doll with her in an attempt to become the first woman to duplicate Charles Lindbergh's transatlantic crossing to Paris.[27]

This popularity persisted. In the tardily 1920s, the U.Due south. Navy's Bombing Squadron Ii (VB-2B) adopted a unit insignia consisting of Felix happily carrying a bomb with a burning fuse. They retained the insignia through the 1930s, when they became a fighter squadron under the designations VF-6B and, afterwards, VF-3, whose members Edward O'Hare and John Thach became famous naval aviators in Globe War II. After the world war, a U.Due south. Navy fighter squadron currently designated VFA-31 replaced its winged meat-cleaver logo with the same insignia after the original Felix squadron had been disbanded. The carrier-based night-fighter squadron, nicknamed the "Tomcatters", remained active under various designations continuing to the present day, and Felix still appears on both the squadron's fabric jacket patches and aircraft, carrying his flop with its fuse burning.

Felix is also the oldest high school mascot in the state of Indiana, chosen in 1926 after a Logansport High Schoolhouse player brought his plush Felix to a basketball game game. When the squad came from behind and won that night, Felix became the mascot of all the Logansport Loftier School sports teams.[28] [29]

When telly was in the experimental stages in 1928, the very commencement image to ever exist seen was a toy Felix the True cat mounted to a revolving phonograph turntable. It remained on screen for hours while engineers used it every bit a test design.[30] [31]

Felix as a behemothic puppet at the 2022 Treefort Music Fest

Over a century after his debut on screen in 1919, he even so makes occasional appearances in pop culture. The pop punk ring The Queers besides use Felix every bit a mascot, often drawn to reverberate punk sensibilities and attributes such as scowling, smoking, or playing the guitar. Felix adorns the covers of both the Surf Goddess EP and the Move Back Home album. Felix too appears in the music video for the single "Don't Back Downwards". Likewise appearing on the covers and liner notes of various albums, the iconic cat likewise appears in trade such every bit T-shirts and buttons. (In an interview with bassist B-Face, he asserts that Lookout! Records is responsible for the utilize of Felix as a mascot.)[32] Felix was originally going to make a cameo in the 1988 film Who Framed Roger Rabbit only the rights for him were not obtained. However he does appear on the tragedy and comedy keystone archway to ToonTown[33] and (as a giant puppet) at the 2022 Treefort Music Fest. For Felix the True cat's 100th anniversary, Universal Pictures dubbed 9 November "Felix the Cat Twenty-four hours" and released new merchandise, including a Pop! figure, Skechers brand shoes, clocks, a PEZ dispenser, shirts, numberless, pillows, and pomade.[34] [35] Too for the anniversary, the National Film and Sound Annal of Australia (NFSA) released an article detailing Felix the Cat's history with frames and clips from early animations.[36]

Comics [edit]

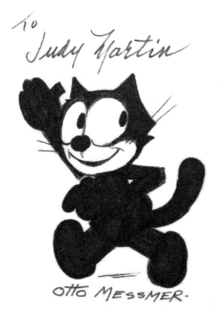

| Felix the Cat | |

|---|---|

An ink drawing of Felix by Otto Messmer dating from around 1975. | |

| Author(s) | Pat Sullivan Otto Messmer (1927–1954) Jack Mendelsohn (1948–1952) Joe Oriolo (1955–1966)[37] |

| Current status/schedule | Daily and Dominicus, ended |

| Launch date | nineteen August 1923 (1923-08-19) |

| End date | 1966 (1966) |

| Syndicate(s) | King Features Syndicate |

| Publisher(southward) | Dell Comics |

| Genre(s) | Humor |

Pat Sullivan began a syndicated comic strip on nineteen August 1923 distributed by Male monarch Features Syndicate.[12] In 1927 Messmer took over drawing duties of the strip.[38] (The first The Felix Almanac from 1924 issued in Great Britain shows the concluding two stories are non the usual Otto Messmer way, so a departure in Pat Sullivan-drawn cartoons tin can be noted.)

Messmer himself pursued the Sunday Felix comic strips until their discontinuance in 1943, when he began eleven years of writing and drawing Felix comic books for Dell Comics that were released every other calendar month. Jack Mendelsohn was the ghostwriter of the Felix strip from 1948 to 1952.[39] In 1954, Messmer retired from the Felix daily newspaper strips, and his assistant Joe Oriolo (the creator of Casper the Friendly Ghost) took over. The strip concluded in 1966.

Felix co-starred with Betty Boop in the Betty Boop and Felix comic strip (1984–1987).

From silent to sound [edit]

With the appearance of synchronized audio in The Jazz Singer in 1927, Educational Pictures, who distributed the Felix shorts at the time, urged Pat Sullivan to make the leap to "talkie" cartoons, but Sullivan refused. Farther disputes led to a break between Educational and Sullivan. Simply after competing studios released the get-go synchronized-sound blithe films, such as Fleischer'southward My Old Kentucky Home, Van Beuren's Dinner Fourth dimension and Disney'due south Steamboat Willie, did Sullivan run into the possibilities of audio. He managed to secure a contract with First National Pictures in 1928. Nonetheless, for reasons unknown, this did non concluding, and then Sullivan sought out Jacques Kopfstein and Copley Pictures to distribute his new sound Felix cartoons. On 16 October 1929, an advertisement appeared in Film Daily with Felix announcing, Jolson-like, "You own't heard nothin' yet!"[ citation needed ]

Felix'south transition to sound was not a smooth one. Sullivan did not advisedly gear up for Felix's transition to sound and added audio effects into the sound cartoons equally a post-animation process.[40] The results were disastrous. More than than e'er, information technology seemed equally though Disney'southward mouse was drawing audiences away from Sullivan's silent star. Not even entries such as the Fleischer-way off-beat Felix Woos Whoopee or the Silly Symphony-esque April Maze (both 1930) could regain the franchise's audience. Kopfstein finally canceled Sullivan's contract. Later on, he announced plans to start a new studio in California, but such ideas never materialized. Things went from bad to worse when Sullivan'due south wife, Marjorie, died in March 1932. After this, Sullivan completely vicious autonomously. He slumped into an alcoholic low, his health quickly declined, and his memory began to fade. He could not even cash checks to Messmer because his signature was reduced to a mere scribble. He died in 1933. Messmer recalled, "He left everything a mess, no books, no nothing. And then when he died the place had to close down, at the height of popularity, when everybody, RKO and all of them, for years they tried to get hold of Felix... I didn't accept that permission [to keep the character] 'cause I didn't take legal ownership of it".[41]

In 1935, Amadee J. Van Beuren of the Van Beuren Studios called Messmer and asked him if he could render Felix to the screen. Van Beuren fifty-fifty stated that Messmer would exist provided with a full staff and all of the necessary utilities. However, Messmer declined his offer and instead recommended Burt Gillett, a one-time Sullivan staffer who was now heading the Van Beuren staff. So, in 1936, Van Beuren obtained approval from Sullivan's brother to license Felix to his studio with the intention of producing new shorts both in color and with audio. With Gillett at the helm, now with a heavy Disney influence, he did abroad with Felix's established personality, rendering him a stock talking creature character of the blazon pop in the day. The new shorts were unsuccessful, and after just three outings Van Beuren discontinued the series, leaving a fourth in the storyboard stages.[21]

Revival [edit]

In 1953, Official Films purchased the Sullivan–Messmer shorts, added soundtracks to them, and distributed them to the home movie and television markets.

Otto Messmer's assistant Joe Oriolo, who had taken over the Felix comic strip, struck a bargain with Felix's new owner, Pat Sullivan'south nephew, to brainstorm a new series of Felix cartoons on television. Oriolo went on to star Felix in 260 television receiver cartoons produced by Famous Studios which was renamed to Paramount Cartoon Studios, and distributed past Trans-Lux showtime in 1958. Like the Van Beuren studio before, Oriolo gave Felix a more domesticated and pedestrian personality geared more than toward children and introduced now-familiar elements such every bit Felix'due south Magic Bag of Tricks, a satchel that could assume the shape and characteristics of anything Felix wanted. The show did abroad with Felix'southward previous supporting bandage and introduced many new characters, all of which were performed past vocalism role player Jack Mercer.

Oriolo's plots revolve around the unsuccessful attempts of the antagonists to steal Felix'due south Magic Purse, though in an unusual twist, these antagonists are occasionally depicted equally Felix's friends too. The cartoons proved popular, but critics have dismissed them equally paling in comparing to the before Sullivan–Messmer works, especially since Oriolo aimed the cartoons at children. Limited animation (required due to budgetary restraints) and simplistic storylines did nothing to diminish the series' popularity.[21]

In 1970, Oriolo gained consummate control of the Felix character and continues to promote the character to this day.

In the belatedly 1980s, after his father's death, Don Oriolo teamed upwardly with European animators to work on the graphic symbol'due south first feature pic, Felix the Cat: The Motion-picture show.[42] In the film, Felix visits an alternate reality forth with the Professor and Poindexter. New Earth Pictures planned a 1987 Thanksgiving release for U.S. theaters, which did not happen;[42] the picture show went direct-to-video in August 1991,[43] which was widely panned upon its release[44] earlier being completely abandoned in the United states during the 21st century. In 1994, Felix appeared on television once again, to replace the pop Fido Dido bumpers on CBS, and then 1 yr afterward in the series The Twisted Tales of Felix the Cat. Baby Felix followed in 2000 for the Japanese marketplace, and also the straight-to-video Felix the Cat Saves Christmas. Oriolo as well brought about a new wave of Felix merchandising, including Wendy'southward Kids Meal toys and a video game for the Nintendo Amusement System.

A Felix prototype in Feline Follies (1919)

Felix was voted in 2004 amidst the 100 Greatest Cartoons in a poll conducted past the British television channel Aqueduct 4, ranking at No. 89.[45]

According to Don Oriolo's Felix the Cat web log, as of September 2008 there were plans in development for a new television series. Oriolo'due south biography page likewise mentions a 52-episode cartoon series and so in the works titled The Felix the True cat Show, which was slated to employ computer graphics.[46] Equally of December 2020, WildBrain is working on a new Felix the Cat serial with Transformers: Rescue Bots and Snoopy in Space co-producers.[47]

Home video [edit]

DVD releases include Presenting Felix the Cat from Bosko Video; Felix! from Lumivision; Felix the Cat: The Collector's Edition from Delta Entertainment; and Before Mickey from Inkwell Images Ink. Some of the Idiot box serial cartoons (from 1958 to 1959) were released on DVD by Classic Media. Some of the 1990s serial has as well been released.

Filmography [edit]

See also [edit]

- Animation in the United States during the silent era

- Baby Felix

- Golden Age of American animation

- Kit-True cat Klock

- Winsor McCay

Notes [edit]

- ^ The Talkies. University of California Press. 22 November 1999. ISBN9780520221284 . Retrieved 1 February 2021.

- ^ ""Felix the Cat" on Records". cartoonresearch.com . Retrieved 4 November 2020.

- ^ "Various Australian Commercials Part 33 (ATV-10, March ten, 1990)". Facebook. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

- ^ "Lani Minella Resume" (PDF). Lani Minella. Retrieved 1 November 2020.

- ^ Cart, Michael (31 March 1991). "The Cat With the Killer Personality". The New York Times . Retrieved 21 August 2009.

- ^ Mendoza, North.F. (27 August 1995). "For fall, a classically restyled puddy tat and Felix the Cat". Los Angeles Times . Retrieved 24 August 2010.

- ^ Barrier, Michael (2003). Hollywood Cartoons: American Blitheness in Its Golden Historic period. Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0-xix-516729-0.

- ^ "Goldenagecartoons.com". Felix.goldenagecartoons.com. Archived from the original on 31 Oct 2013. Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ^ TV Guide Book of Lists . Running Press. 2007. p. 158. ISBN978-0-7624-3007-nine.

- ^ McNary, Dave (17 June 2014). "DreamWorks Animation Buys Felix the Cat". Variety . Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ^ Solomon, 34, says that the character was "the as yet unnamed Felix".

- ^ a b c Solomon 34.

- ^ "Felix exhibition guide (archived)" (PDF). webarchive.nla.gov.au. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 Oct 2007. Retrieved two September 2017.

- ^ a b "All Media and legends...A thumbnail dipped in tar". Vixenmagazine.com. Archived from the original on 27 September 2008. Retrieved 14 September 2008.

- ^ "Rewind (ABC TV): Felix the True cat". Abc.net.au. 3 March 1917. Archived from the original on 8 February 2012. Retrieved x March 2014.

- ^ a b Sammond, Nicholas (2015). Birth of an Industry: Greasepaint Minstrelsy and the Rising of American Animation. Durham. p. 71. ISBN978-0822375784.

- ^ Barrier 29 and Solomon 34.

- ^ Barrier 1999, p. thirty.

- ^ a b c Solomon 1994, p. 34.

- ^ "English language: Publicity photo National Broadcasting Company (NBC) issued for their 30th ceremony in 1956. The photograph depicts their work in boob tube kickoff in 1928. The Felix the Cat doll shown in the photograph was used by the visitor for over a decade beginning with mechanical television in 1928 and continued to be used to help develop electronic television". 4 December 1956.

- ^ a b c Solomon 37.

- ^ For instance, Solomon, 34, quotes Marcel Brion on these points.

- ^ Solomon 1994, p. 36.

- ^ Heritage Auctions: completed auctions, 9 August 2009 and was subtitled "Pat Sullivan's Famous Creation in Song."

- ^ "Laokay.com". Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ^ Los Angeles, CA (1 January 1970). "maps.google.com". Goo.gl . Retrieved 10 March 2014.

- ^ Canemaker, John (1991). Felix: the twisted tale of the world'south most famous cat. Pantheon Books. p. 118. ISBN067940127X.

- ^ "History of Mascot Felix the Cat". lhs.lcsc.k12.in.us. Logansport Loftier School. Archived from the original on 22 March 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ Viquez, Marc (10 June 2020). "How Felix the Cat Became This High Schoolhouse's Mascot". SportsLogos.Internet News. Archived from the original on 18 June 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ "The First Star of Television". Museum of Television . Retrieved ix August 2018.

- ^ Shedden, David (vii November 2014). "Today in Media History: In 1928 Felix the Cat began testing a new tech called television". Poynter . Retrieved 9 Baronial 2018.

- ^ "The Queers – Interviews". Thequeersrock.com. Archived from the original on nine March 2008. Retrieved xiv September 2008.

- ^ "Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988)". IMDb . Retrieved 2 September 2017.

- ^ Brook, Jerry (28 October 2019). "Universal Celebrates 100 Years of "Felix The Cat"". Animation Scoop. Archived from the original on 31 October 2019. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ Knight, Rosie (ix Nov 2019). "Gloat 100 Years of Felix the True cat with a New Line of Merch". Nerdist. Archived from the original on 11 November 2019. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ Bondfield, Mel (five November 2019). "100 Years of Felix the Cat". www.nfsa.gov.au. National Film and Sound Archive of Australia. Archived from the original on 26 June 2020. Retrieved 27 September 2020.

- ^ "Oriolo entry". Who's Who of American Comic Books, 1928–1999 . Retrieved 18 November 2018.

- ^ Messmer entry, Who's Who of American Comic Books, 1928–1999. Accessed 18 Nov. 2018.

- ^ Mendelsohn entry, Who's Who of American Comic Books, 1928–1999. Accessed eighteen November. 2018.

- ^ Gordon, Ian (2002). "Felix the Cat". St. James Encyclopedia of Pop Civilisation. Archived from the original on 28 June 2009.

- ^ Quoted in Solomon 37.

- ^ a b Cawley, John; Korkis, Jim (1990). Drawing Superstars. Pioneer Books. pp. 88–89. ISBN1-55698-269-0 . Retrieved fourteen June 2010.

- ^ "New on Video". Beacon Periodical. 23 Baronial 1991. p. D21. Retrieved 14 June 2010.

- ^ Gritten, David, ed. (2007). "Felix the Cat: The Movie". Halliwell's Pic Guide 2008. Hammersmith, London: HarperCollins Publishers. p. 401. ISBN978-0-00-726080-v.

- ^ "The 100 Greatest Cartoons". Channel four. Archived from the original on 6 March 2005. Retrieved 20 February 2013.

- ^ "Donsfelixblog.com". Donsfelixblog.com . Retrieved ten March 2014.

- ^ "thenerdstash.com".

References [edit]

- Barrier, Michael (1999). Hollywood Cartoons: American Animation in Its Golden Age . Oxford University Press. ISBN978-0-1980-2079-0.

- Beck, Jerry (1998). The 50 Greatest Cartoons. JG Press. ISBN978-1-5721-5271-vii.

- Canemaker, John (1991). Felix: The Twisted Tale of the Globe's Most Famous True cat. Pantheon, New York: Da Capo Printing. ISBN978-0-3068-0731-ii.

- Crafton, Donald (1993). Before Mickey: The Animated Picture 1898–1928. Chicago: University of Chicago Printing. ISBN0-226-11667-0.

- Culhane, Shamus (1986). Talking Animals and Other People . St. Martin's Printing. ISBN978-03068-0830-2.

- Gerstein, David (1996). 9 Lives to Live. Fantagraphics Books.

- Gifford, Denis (1990). American Animated Films: The Silent Era, 1897–1929. McFarland and Visitor. ISBN0-8995-0460-four.

- Maltin, Leonard (1987). Of Mice and Magic: A History of American Animated Cartoons. Penguin Books. ISBN978-0-4522-5993-five.

- Solomon, Charles (1994). The History of Animation: Enchanted Drawings. Outlet Books Visitor. ISBN978-0-394-54684-1.

Further reading [edit]

- Patricia Vettel Tom (1996): Felix the Cat as Modern Trickster. JSTOR 3109216 American Art, Vol. 10, No. 1 (Spring, 1996), pp. 64–87

External links [edit]

- Official website

- Felix the True cat at Don Markstein's Toonopedia. Archived from the original on 15 July 2016.

- Pat Sulivan at the Internet Archive.

- The Archetype Felix the Cat Page at Gilded Age Cartoons

- Felix the True cat (Pat Sullivan) at the Big Cartoon DataBase

- Australian Broadcasting Corporation, 2004, Rewind "Felix the Cat" (Concerns the dispute over who created the character.)

- "Country Library of New Due south Wales, 2005, "Reclaiming Felix the Cat"" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 October 2006. (768 KiB). Exhibition guide, including many pictures.

Source: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Felix_the_Cat

0 Response to "automobile design 3d drawing 2000 felix kings canyon middle school"

Post a Comment